PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Sub-Saharan Africa has long been known to have the highest rates of HIV/AIDS in the world. But a new study published in this month’s issue of PLOS One reveals that despite the focus on the region, few estimates exist of one of its most vulnerable populations: children living in households with HIV-infected adults.

While researching a separate project in Lesotho, Susan Short, professor of sociology, faculty associate of the Population Studies and Training Center at Brown University, and the lead author on the paper, was surprised to discover that as many as 50 percent of the children in that country either lived in households with someone who had tested positive for HIV/AIDS or were orphaned, most by the disease. They were aware of widely published statistics on orphan status, but had not seen estimates for Lesotho of children’s experiences living with HIV-infected adults. The discovery pushed Short to look more deeply at the issue.

“This was such a powerful reminder of the current sustained impact of the epidemic on families and children despite the wonderful progress reducing infections and improving treatment recently,” Short said.

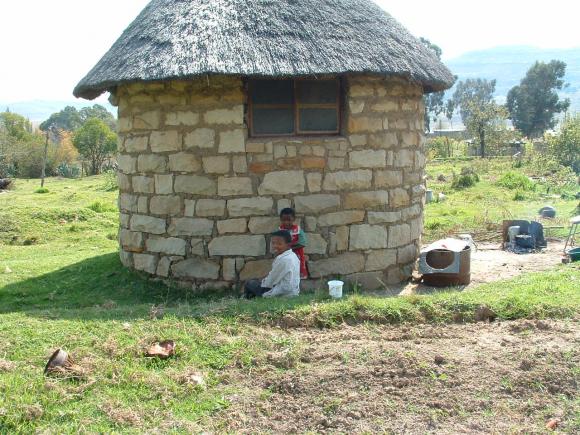

Health care workers in Sub-Saharan Africa face many challenges to keeping children healthy, including extreme poverty and high levels of disease and illness. The emergence of HIV and AIDS in the region has only exacerbated these challenges.

Short and her collaborator, Rachel Goldberg of the University of California–Irvine, wanted to take a closer look at how common it was for children to live in a household with at least one HIV-infected adult. Some of these children may have needs that are distinct from other HIV-affected children. They can have increased exposure to opportunistic infections — such as tuberculosis and pneumonia — and they can be affected by a cascade of events in their households including the diversion of attention and other resources, a change in household responsibilities including the need to provide care, and effects of HIV-associated stigma in schools or communities.

Using demographic and health survey data from 23 countries collected between 2003 and 2011, the team of researchers estimated the percentage of children living in a household with at least one HIV-infected adult. They also looked at how those numbers overlapped with the number of orphans in the region, as well as the relationship between children and the adults who are infected in their households.

They found that the population of children living in a household with at least one HIV-infected adult is substantial where HIV prevalence is high and is largely distinct from the orphan population. In southern Africa, the percentage of children living in a household with at least one HIV-infected adult exceeded 10 percent in all countries and reached as high as 36 percent. Most of those children live with parents, often mothers, who are infected, and in most countries more than 20 percent live in households with at least one infected adult who is not a parent.

“We were surprised to find that while children living in households with HIV-infected adults are widely recognized as HIV-affected, most publications that monitor the situation of children in the context of AIDS report only on the prevalence and incidence of pediatric HIV, the percentage of HIV-infected pregnant women receiving treatment, and the prevalence of children who have lost one or both parents to AIDS or other causes,” said Short. “Of course, these are all very important indicators. But there is so much more to know about children’s experiences.”

The authors note that in the early stages of the epidemic, data to produce these estimates were not available. HIV testing was being done in clinics and could not easily be linked to data on families and children. “It made sense that when looking at children in families, we would start by producing indicators of orphan status. The data were available,” said Short.

The researchers predict that these numbers will not decrease any time soon and conclude that current care and outreach efforts should be examined to assure that the distinct needs of these children are being met.

“We are optimistic that by providing these numbers we are contributing in some small way to efforts underway to support HIV-affected children. The number of children living in households with HIV infected adults in high HIV prevalence areas is substantial,” said Short.