PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] —Nowadays, salamanders are extraordinary among modern four-legged vertebrates: Repeatedly and throughout their lifespan, they can regenerate limbs, tails, and internal organs that were injured or lost due to amputation.

They are also special in the way their legs form during embryonic development. Generally limb development follows the same process in all four-legged vertebrates — from frogs to humans — despite the enormous variety of forms and functions that vertebrate limbs have.

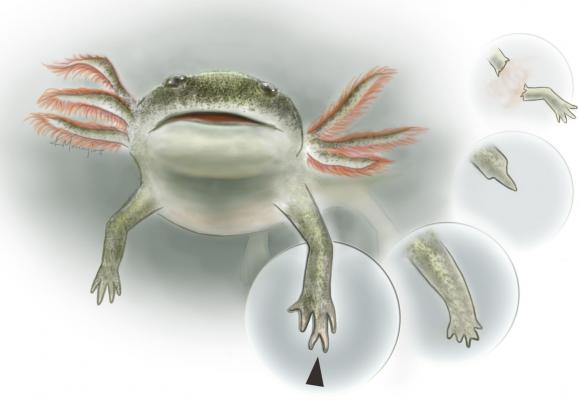

“Salamanders, on the contrary, form their fingers in a reversed order compared to all other four-legged vertebrates, a phenomenon that has puzzled scientists for over a century,” said lead author Nadia Fröbisch of Museum für Naturkunde. “The question that we wanted to address was if and how this different way of developing limbs is evolutionarily linked with the high regenerative capacities.”

So the team, including co-author Florian Witzmann, visiting scientist in Brown’s Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, set out to study fossils from about 300 million years ago to see how the capacity developed. The fossils used in the study, which appears in Nature, derive from the collections of a number of natural history museums including the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin.

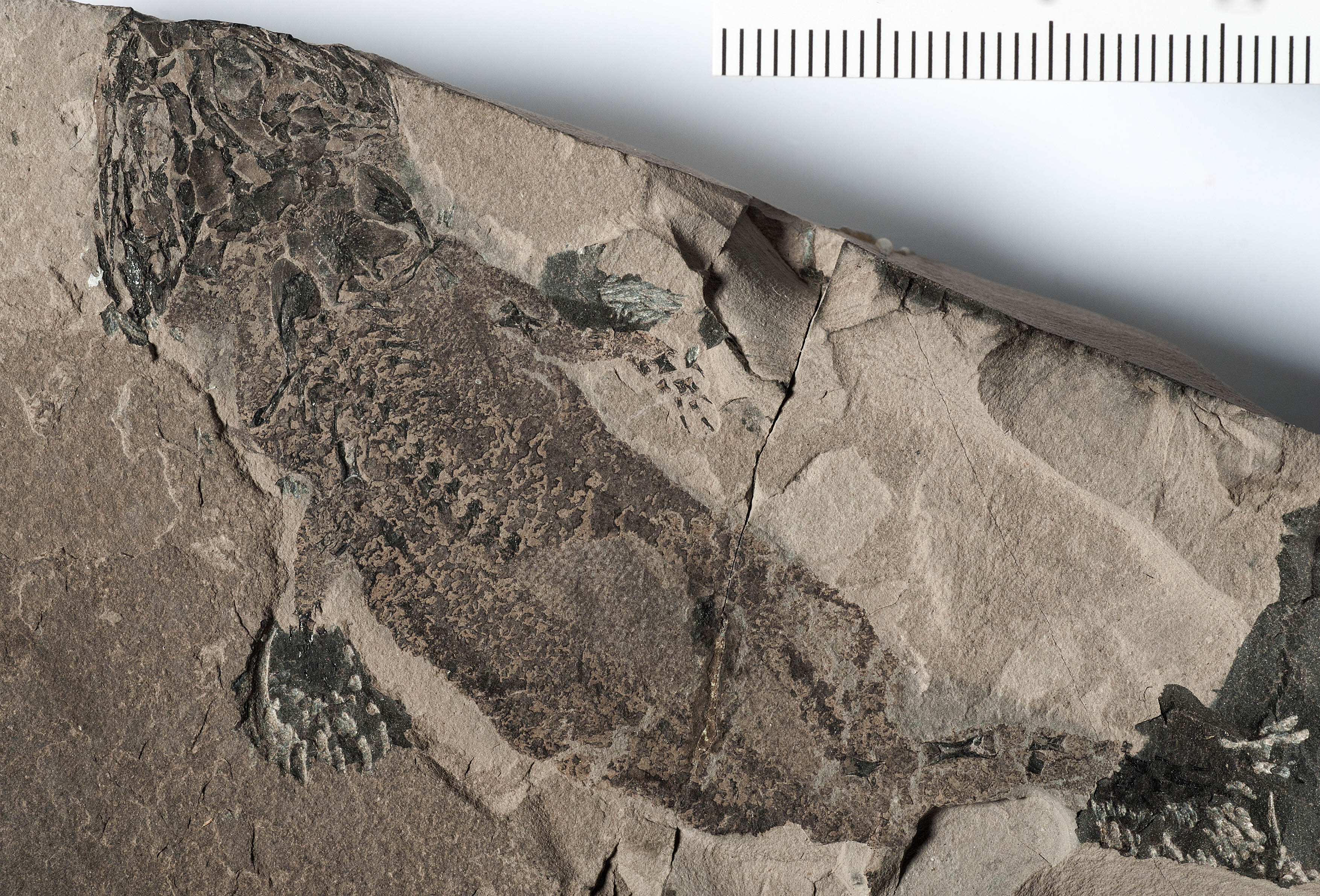

“The amphibians fossilized under excellent conditions for preservation and are represented by a large number of individuals and developmental stages,” Witzmann said. “This extraordinary fossil record allowed for the detailed study of limb development and regeneration.”

Well-preserved fossils, such as this Micromelerpeton credneri, allowed researchers to track the evoluton of regeneration. Image: Hwa-Ja Götz/MfN Berlin

In their studies the authors investigated different amphibian groups of the Carboniferous and Permian periods and showed that different groups were able to regenerate their legs and tails in a way that previously was exclusively known from modern salamanders.

“We were able to show salamander-like regenerative capacities in fossil groups that develop their limbs like the majority of modern four-legged vertebrates as well as in groups with the reversed pattern of limb development seen in modern salamanders,” said co-author Jennifer Olori of the State University of New York at Oswego.

That means that back then, it wasn’t just salamanders but many creatures that had the capacity to regenerate.

“The fossil record shows that the form of limb development of modern salamanders and the high regenerative capacities are not something salamander-specific, but instead were much more widespread and may even represent the primitive condition for all four-legged vertebrates,” said Fröbisch. “The high regenerative capacities were lost in the evolutionary history of the different tetrapod lineages, at least once, but likely multiple times independently, among them also the lineage leading to mammals.”