PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Whenever in their careers Alpert Medical School students encounter a patient with a rare disease, it may rekindle the empathy and insight they can glean from the portraits of more than 20 people — mostly children — that hang on the medical school building’s walls this month.

There’s Austin, who drums and loves spicy food, and younger brother Max, who loves building with Legos. They have Duchenne muscular dystrophy, a degenerative neuromuscular disease. There’s Harper, a little girl who loves touching her baby brother and getting kisses from the family dog, at least sometimes. She has Angelman’s syndrome, an autism-like disorder.

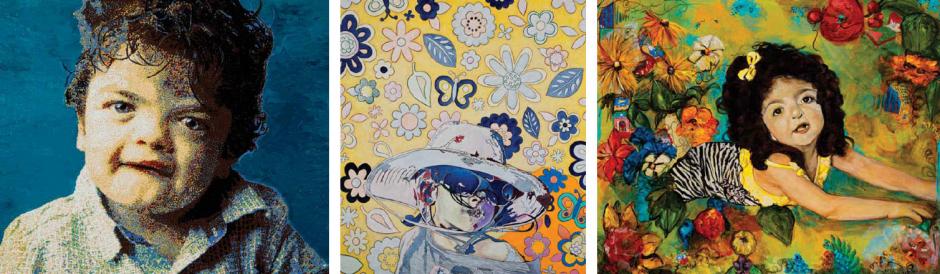

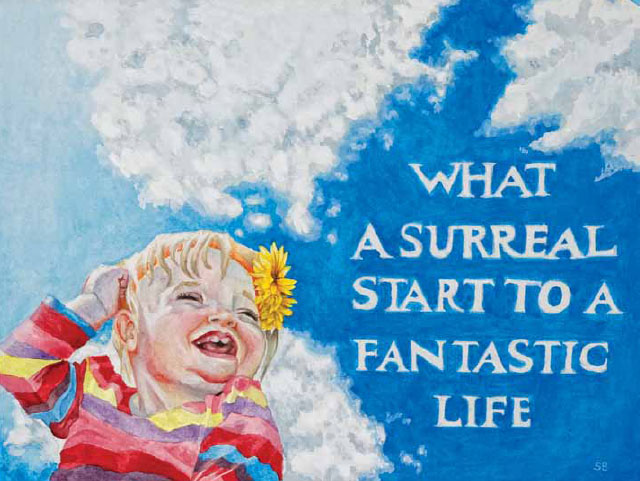

In “Beyond the Diagnosis,” staged by the Rhode Island-based Rare Disease United Foundation, each painting and drawing produced by professional artists depicts not a case or a disease but a person. They are individuals living necessarily extraordinary lives to their fullest as best they can with loving families working hard by their side. It can be too easy for doctors to overlook or even dismiss that.

“Everyone is characterized as a disease,” said Dr. Craig Eberson, a surgeon and associate professor of orthopaedics who is also a member of the foundation board. “We’re all guilty. I can picture a case. I can picture the X-rays. I can picture all the screws I put in but then ‘What’s that kid’s name again?’

“But realize that you have an interaction with a patient for 15 minutes and they have what they have for their entire life,” Eberson said.

The exhibit premieres here during Rare Disease Month, but it will go on display in other medical schools, said organizer Patricia Weltin, executive director of the foundation. More students and doctors, then, can be introduced to patients with rare diseases in the proper human context. Their lives are ones of considerable struggle and often a feeling of being invisible or lost.

Wetlin, who has two daughters with both hypermelanosis of Ito and Ehlers Danlos syndrome, works to change that with the foundation and this exhibit.

“You get to see the spirit of these people and not just their illness,” she said. “I talked to one of the students while we were setting it up [Feb. 4], and she was looking at a painting. I asked, ‘What do you see?’ and she said, ‘I see a beautiful little boy’ and I said, ‘That’s what we want you to see.’”

The artists donated their works, Weltin noted.

“I have never worked with a group of people not connected to rare [diseases] that have put their hearts so fully into a project,” she said. “They are truly extraordinary.”

Meet Truman

The exhibit arrived at Brown with some serendipity. Weltin proposed the exhibit to Eberson, who treats her daughters and has worked with her to arrange lectures to medical students. He suggested it to the medical school last summer.

The task came to Kris Cambra, director of biomedical communications, who has taken on the task of managing rotating art displays in the building. The first, a show of artistically stained placental cells by Yale professor Harvey Kliman, ran from last October to this month. Cambra is now working with students on an exhibit to feature their works. But in the case of “Beyond the Diagnosis,” she didn’t just help the art find its way onto the walls. Her son Truman is the subject of one of the portraits. He has a rare disease and through this process, Cambra and Weltin learned of each other.

Truman, like many 8-year-old boys is an avid video game player who also loves gym class. That flies happily in the face of a main symptom of Williams syndrome: a circulatory system that lacks the protein elastin, leaving his vessels constricted and less stretchy. He faces a likely lifetime of high blood pressure. The syndrome also affects the brain, meaning he has difficulty processing spatial information. Nevertheless, he loves to play ball.

“We’ve moved on to looking at what his strengths are and just being really happy about those and fostering those things,” Cambra said.

Truman is a charmer. An energetic, musical and surprisingly eloquent (despite a lower IQ) second grader, he hugs people in the supermarket and once looked up at a woman that he and his mom encountered in the ladies room and announced, “Hi. You’re my girlfriend!” The woman, Cambra said, responded “That’s the nicest thing anyone’s said to me all day.”

In April, Truman will undergo another corrective surgery to re-widen key blood vessels around the heart. It won’t cure anything, but the procedure will maintain better circulation for longer.

Teaching doctors to learn

The uncommon degrees of joy and work and pain and personal research that come with having a loved one with a rare disease should never be lost on the doctors who join the family’s care team, Cambra said.

“I want everybody to have the same experience that we had with my pediatrician,” Cambra said. “When we got the diagnosis in Boston from the geneticist we went back to her. She said, ‘I knew one patient in my residency training that had Williams syndrome,’ but she never had one in her practice. She said I’m going to study I’m going to take all the information that the doctors in Boston have sent me and literally she said to her medical assistant, ‘Keep this file aside. I need to come back to this. I’m going to learn everything that I need to know about taking care of Truman. We’re going to do this together.’”

Eberson agreed that when he treats patients with rare diseases, such as Weltin’s daughter Hana, it has to be in collaboration with the patient and the family. They are experts.

“There can be a lot of insecurity on the part of a physician or a medical student because you are supposed to be the smartest person in the room,” said Eberson. “So what we see are two types of interactions. One is the brush-off where you say, ‘This is a know-it-all,’ or one of those patients or one of those parents and you become closed-minded and miss an opportunity. Or you see the type of physician who says, ‘I’m going to do some research and talk to some people who’ve had some experience and together we can make a good decision for your child.’”

In medicine that’s a counterintuitive but necessary lesson: Sometimes what you learn is to be more humble about what you don’t yet know. But it’s true. Especially in rare cases.