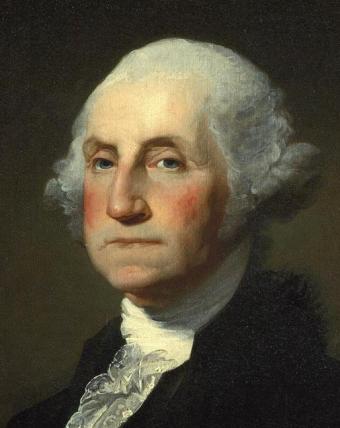

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Brown President Christina Paxson visited Touro Synagogue in Newport Sunday, Aug. 17, 2014, to deliver the keynote address at the annual reading of President George Washington’s Letter to the Hebrew Congregations of Newport.

That letter of thanks, written after Washington’s 1790 visit to Rhode Island, describes the new nation’s dedication to religious liberty and the pursuit of a democratic ideal that involves all citizens equally.

Touro Synagogue is the nation’s oldest surviving synagogue, opened in 1763, making it roughly contemporaneous with Brown. (The first meeting of the Brown Corporation took place in Newport in early September 1764.)

Photo: Sam Shamoon

In her address, Paxson touched on themes that Brown, Washington, and the Touro Synagogue held in common including, as the Brown Charter of 1764 put it, the “full, free, absolute, and uninterrupted liberty of conscience” and access “to the equal advantages, emoluments, and honors of the ... University ... [and] a like, fair, generous, and equal treatment.”

Washington’s brief letter — 340 words — assured the members of Touro that the future would be built not only on religious toleration, but on religious liberty:

May the children of the stock of Abraham who dwell in this land continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other inhabitants — while every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and fig tree and there shall be none to make him afraid.

Touro Synagogue Keynote Address

1 p.m. Sunday, August 17, 2014

(Text as prepared for delivery)

I am honored to be here with you today in this remarkable place, to celebrate something both simple and extraordinary: a letter from the first president of the United States to the Touro Synagogue, confirming in 340 words that Jews would be free to practice their faith, without fear, as full citizens in the newly formed country.

Even more extraordinary, the letter makes plain that this was not a special gift given to Jews alone. Instead, Washington expressed the idea of liberty of conscience as a universal principle that would be applied to all citizens.

This event is meaningful to me, both professionally and personally. Professionally, because Brown is in the midst of celebrating the 250th anniversary of its founding — a founding which reflects the very same sentiments that are expressed in Washington’s letter. Personally, because I suspect that this is the first time a Jewish woman named “Christina” has had the privilege of speaking from this podium!

Let me start with the personal. I was raised as a Quaker, and during my childhood I attended Sunday School at the Pittsburgh Friends meeting. This was not your typical Sunday School. I grew up in the turbulent time of the 1960’s and early 1970’s, when the country was grappling with civil rights, women’s rights, labor rights and the Vietnam War — issues that were very important to the Friends.

My recollection from Sunday School is that we learned more about Martin Luther King than Jesus. I vividly remember reading Mahatma Gandhi’s autobiography, but we spent little time on the Bible. We discussed what it meant to be a conscientious objector; considered whether pacifists were obliged to put U.S. income tax payments into escrow, lest they inadvertently support war; and debated the merits and limitations of civil disobedience.

The Friends had strong convictions about pacifism and social justice. But, although I didn’t appreciate it at the time, I realize now that I was never told what I should believe. I was free to listen, learn and disagree if I chose to do so.

The overarching lesson — the most important lesson — was that convictions about matters of conscience should grow from personal introspection, informed by discussion and debate, rather than be dictated by religious doctrine.

So, how did I come to be a Jewish woman named Christina? It’s simple: I fell in love. I met my husband, Ari Gabinet, at Swarthmore College in the fall of my freshman year. I converted to Judaism as a senior in college, after Ari and I became engaged. One reason for my conversion was my deep love and respect for Ari’s family. But that wasn’t the only factor. At least the way my new family practiced it, Judaism was a religion that welcomed questioning, quarreling and intellectual debate. In the end, and somewhat ironically, it was the lessons I had learned in Quaker Sunday School that made me feel very comfortable taking on a new Jewish identity.

These lessons have also helped me in my role as president of Brown University. As many of you know, Brown University dates its founding from 1764, partly because the first meeting of the Corporation of Brown University was held here in Newport in September of 1764, not far from this spot. From the time of its founding, 250 years ago, Brown has embodied the ideals central to the founding of Rhode Island: tolerance, openness, and intellectual freedom. These are the very ideals that made it possible for the Touro Synagogue to flourish here in Newport, even before the establishment of the United States.

The Baptists who founded Brown appreciated the wisdom of this philosophy. They crafted a remarkable charter for the new college, which declared that students from all religious backgrounds would be welcome at Brown. Specifically, the charter says that:

“... into this liberal and catholic institution shall never be admitted any religious tests. But, on the contrary, all the members hereof shall forever enjoy full, free, absolute, and uninterrupted liberty of conscience ...”

The charter goes on to say that “youth of all religious denominations shall and may be freely admitted to the equal advantages, emoluments, and honors” of the university, and that “all religious controversies may be studied freely, examined, and explained.”

In 1770, the Corporation of Brown University was asked by a subscriber whether this religious openness applied to Jews. To clear up any doubt, the Corporation responded by passing a resolution stating that “the Children of Jews may be admitted into this Institution and entirely enjoy the freedom of their own Religion, without any Constraint or Imposition whatever.”

I think it is fascinating that the section of Brown’s Charter on religious freedom concludes with the statement that “above all, a constant regard be paid to, and effectual care taken of, the morals of the College.” During this time period, many might have thought that a laissez-faire attitude toward religion would go hand-in-hand with a lack of concern about moral development. However, the founders of Brown appreciated that an education on matters of morality was consistent with — even enhanced by — healthy debate about matters of conscience.

Although the Brown Charter was path-breaking for its time, it was far from perfect by modern-day standards. Just like George Washington’s letter to the Touro Synagogue, the Brown Charter restricted its attention to religious liberty. Although it was open to students of all faiths, it specified that the professors and officers of the Corporation should be Protestant, and that the President should be a Baptist. (Fortunately, Charters can be amended.) Furthermore, the Rules of the College indicated that atheists were not welcome as students.

However, like George Washington’s letter, the Charter established a principle that supports the much broader vision of liberty and inclusion that we enjoy today. Brown’s students now include men and women; Americans and citizens from countries across the globe; and students who are from just about every race and ethnicity imaginable. Although I am fairly sure that Brown had gay students long before the letters LGBTQ had meaning, all of our students now can be openly proud of their identities.

Brown’s openness extends to the way we teach and learn. In the late 1960’s, two Brown students — Ira Magaziner and Elliot Maxwell — led a movement to reform the Brown curriculum. Their goal was to instill a new way of thinking about education: one in which students were encouraged to chart their own educations. The famous “open curriculum” at Brown imposed no distribution requirements and had no core curriculum. To encourage students to be intellectually adventurous — to go into territory that might be foreign or intimidating — students could take as many courses as they wanted on a pass-fail basis. Although there have been some modifications over the years, students are still given remarkable freedom to be intellectual entrepreneurs.

An unanticipated benefit of the new curriculum is that it has attracted a faculty that pushes the boundaries of knowledge — mapping new terrain in their fields of study and frequently crossing borders into other disciplines. This approach has produced innovative scholarship in areas as diverse as brain science, international development, and global approaches to the humanities.

I know that some look at the Brown curriculum with skepticism or worse: How can students ever hope to get a good education without being told what to study? Don’t we need to provide them with a clear roadmap to a well-rounded education? A Brown professor named Matthew Guterl, in a blog published by the Chronicle of Higher Education, explained Brown’s approach this way. He said: “The problem is that anyone can follow a map, even if the route is hard. Making a map, though, is tougher.” Brown’s approach demands that students undertake the difficult task of making their own intellectual maps — not by being told what to think, but by being taught how to think.

I am not advocating for all universities and colleges to follow Brown’s model. A great strength of the American system of higher education is that students and their families have a wide range of options from which to choose, with different sizes, styles, and approaches to education.

But I do believe that, no matter how they structure their curricula, it is essential for colleges and universities to promote and encourage the free and open exchange of ideas. This is not just a matter of students’ intellectual development but also — reflecting back to the words of Brown’s charter — their moral development. If colleges and universities (and, I would argue, middle schools and high schools) create and sustain communities that foster freedom of expression and debate on matters of conscience, it will be to the benefit of the community, the nation and the world.

It is not easy to create successful societies that welcome tolerance, openness and intellectual freedom — whether on college campuses or in states or nations. Think back to the founding of this state, when King Charles II granted the colony of Rhode Island a charter “to hold forth a livlie experiment.” This choice of words is telling. As we know, experiments are inherently risky. Success is not guaranteed. The use of the word “lively” suggests that, regardless of success or failure, the experiment is unlikely to proceed smoothly, but will instead generate some tense moments. Not surprisingly, through its history, Rhode Island was a place of lively and sometimes contentious debate about the most important issues of the day: independence from Britain; slavery; voting rights of immigrants; and, most recently, same-sex marriage.

The same is true on college campuses. Universities are crucibles where new and sometimes conflicting ideas about social and political issues are expressed, develop, and evolve. This can produce tension within our communities, and recently we have seen freedom of expression come under attack. This occurred at Brown last year, when then-New York City Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly was prevented from speaking due to interruptions from students and community members who objected to stop-and-frisk policing and racial profiling. And it occurred during graduation season at college campuses across the country, when students objected to commencement speakers who had ideas with which they did not agree.

I confess that I have mixed reactions to these events. I do not object to protest — remember, I was raised learning about civil disobedience. I’m glad that students are aware enough, and care enough, about the world around them to have formed convictions about important social issues. But I do object, strongly, when these convictions lead to protest that suppresses the free exchange of ideas.

As educators, we must perform a balancing act. On one hand, we do not want our students to be apathetic. We encourage them to care deeply about matters of social justice, and to act on their convictions. On the other hand, we need to teach the lessons of open-mindedness and tolerance that characterize a free society. When zeal for promoting social justice comes into conflict with tolerance and respect, we must carve a careful path between the two: to honor the ideals of those who desire to act on matters of conscience, while helping them understand that behavior that suppresses freedom of expression of others does not serve our society well.

Perhaps the simple lesson here is that the cost of freedom of expression in a diverse society is that … people express themselves, sometimes in ways that rub their neighbors the wrong way. But the benefits of a tolerant society — the kind of society George Washington and his colleagues mapped out when Brown and Touro were still new — are infinite. I am glad that the Touro Synagogue stands as a symbol of liberty and tolerance to which we continue to aspire.

Thank you.