PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — The piece of unidentified reptile skin sits neatly folded in a display case in Rhode Island Hall, a leather mosaic of thick scales. Around it lie equally curious artifacts: small stuffed birds, a rusty candle snuffer, the preserved lungs of a Gila monster.

It’s not the first time these disparate objects have resided together. More than 100 years ago, they called this same space home, when it was Brown’s Museum of Natural History and Anthropology. Then, dozens of wood and glass display cases lined the walls, filled with all manner of creatures large and small. When the museum, deemed old-fashioned and too costly, was closed in the early 1900s, its specimens were boxed up and carted off to storage spaces around campus. In 1945, ninety-two truckloads of objects were brought to the University dump on the banks of the Seekonk River, never to be seen again. Only about 600 pieces survived.

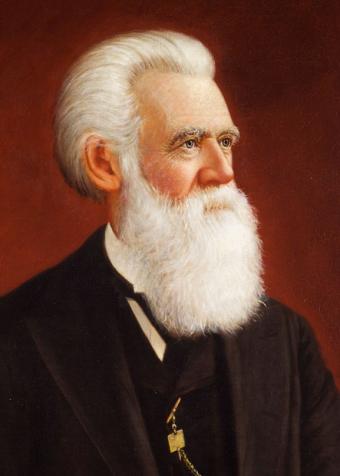

Now a group of students, faculty, and other collaborators is trying to preserve what little remains of that museum and the legacy of its founder, John Whipple Potter Jenks. The group’s new exhibition, “The Lost Museum,” is on display through May 2015 in Rhode Island Hall. The exhibition is part of the University’s 250th anniversary celebration.

The group — The Jenks Society for Lost Museums — has been working tirelessly for more than a year, researching the former museum and cataloging the surviving objects. They also took a trip to the former dump site in hope of finding remnants of the museum. They walked away with a piece of skunk jaw, a fragment of a stone sculpture and a small bottle of dirt. The pieces are displayed in “The Lost Museum,” a tribute to the site, and what remains buried under decades of dirt.

“We hold no assumptions that any of these came from the original museum,” said Lily Benedict, who will receive her master’s degree in public humanities at Commencement ceremonies May 25. “In all likelihood, nothing is recoverable.”

Though they have varying academic interests, the students were inspired to create the exhibition by their mutual fascination with the story of the museum and its demise. “It’s such a rich story,” said Jessica Palinski, a first-year master’s degree student in the public humanities program.

The group of 10 students, which includes seven public humanities graduate students and three RISD students, teamed up with artist Mark Dion to reimagine the vanished museum with a contemporary twist.

“It’s a science, art, and history story all in one,” said Steven Lubar, professor of American studies, who is the faculty supervisor on the project.

In addition to the display case of original museum artifacts, two small rooms off the Rhode Island Hall lobby showcase other aspects of the museum’s history. Past the modern-looking plaque that reads “J.W.P. Jenks, Naturalist, 110,” is a recreation of what Jenks’ office might have looked like on the day in 1894 when he collapsed and died on the steps of Rhode Island Hall. Using an article one of Jenks’ students wrote for The Atlantic titled “A Bed in the Museum” as their guide, the students pieced together the artifact-filled office, taking liberties to insert subtle clues about his life and work. A copy of Darwin’s Theory of Evolution, sits under a chamberpot, a nod to Jenks’ anti-Darwinist beliefs, while an ax hints at a near-death experience he had as a child.

In contrast to the dark, artifact-filled office, a less cluttered space across the way makes up the exhibition’s third part. There, shelves filled with all-white recreations of once-existing artifacts reach from floor to ceiling. The students commissioned the works mostly from local artists, asking each to create a piece. The result is a mix of natural history specimens, ethnographic objects, and other curiosities. The museum’s acquisition logs couldn’t be found, so the students used old photos, annual reports, and newspaper articles to determine what items once lined the display cases. The monochromatic theme was chosen so that visitors wouldn’t mistake the new pieces for lost originals. They’re a nod to what might have been.

“These are the ghosts of the museum,” Lubar said.

“The Lost Museum” will be on display in Rhode Island Hall through May 2015, with several events and programs scheduled throughout the 2014-15 academic year. More information is available at the Jenks Museum site.