PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] —The David Winton Bell Gallery will present Building Expectation: Past and Present Visions of the Architectural Future from Saturday, Sept. 3, through Sunday, Nov. 6, 2011. Exhibition curator Nathaniel Robert Walker will deliver a lecture titled "Industria, Here and Now," at an opening reception on Friday, Sept. 9, 2011, beginning at 5:30 p.m. in the List Art Center auditorium. The exhibition and opening event are free and open to the public.

Building Expectation presents a collection of historic and ongoing visions of the future from the 19th century until the present day. The focus of the show is less upon canonical designers or art-historical movements and more upon broadly based, popular speculation in the public sphere, according to Walker, a Brown graduate student in the history of art and architecture. The exhibition’s content has been drawn from a number of university libraries and private collections, as well as the Swiss state-supported museum of utopia known as the Maison d’Ailleurs (House of Elsewhere). Many of the objects have never been exhibited in the United States.

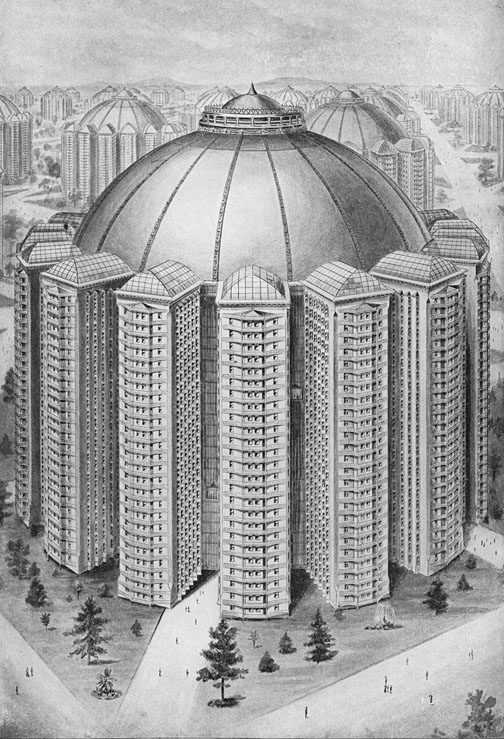

“The world of tomorrow has usually been imagined first and foremost as a place — the new Promised Land, the millennial landscape. And architecture, cast since the Enlightenment as the calling card for cultural and technological periods in the grand narrative of human development and progress, has always been one of the future’s most revealing and recognizable features,” said Walker.

The final portion of the exhibition is dedicated to contemporary visions of the future, chosen or commissioned for their makers’ ability to continue the critical conversation about the “world of tomorrow.” A number of the participants offer futuristic design paradigms that openly defy some of the most persistent dogmas of progressive Modernism, while others take the conceptual processes of technological evolution to their furthest extremes. All of them call into question those aspects of “the future” that have been, and often still are, taken for granted. Artists such as Pippi Zornoza, Jane Masters, and Brian Knep, all based in New England, have created large installations that are architectural in their scope as well as their content. Others such as Swiss artist Christian Waldvogel and the urban design firm DPZ are showing works resulting from years of study and refinement in sites around the world.

Spanning the gap between past visions and contemporary concepts of the future is a new drawing by illustrator Katherine Roy. It depicts the wonderful but deeply troubled city of Industria, a radiant urban landscape described in the largely forgotten 1884 novel Ignis by Comte Didier de Chousy. "A fevered, delirious paradise, it is the stage for a satirical tragic comedy of utopian proportions, and Roy’s illustration speaks on multiple levels to the past and ongoing cultural processes that may be said to “build expectation,’” Walker said.

The Bell Gallery, located inside List Art Center, 64 College St., is open to the public without charge Monday though Friday from 11 a.m. until 4 p.m. and 1 to 4 p.m. on Saturday and Sunday. For more information, please call 401-863-2932.